If you like hockey, you may be interested in watching Red Army. It takes you back to a dynasty in sports history hockey fans will remember well.

The film focuses on the glory days of Soviet hockey. It doesn’t focus so much on its first exposure of Soviet hockey prowess back during its early days starting with the 1956 Winter Olympics and continuing in the 1960’s. Its prime focus however was during the 70’s and 80’s when Soviet hockey was at its best and most dominating. This was the era of Vladislav Tretiak who is widely considered to be the best goalie in the history of ice hockey. This was also the era of Vyacheslav ‘Slava’ Fetisov and the magic five that included him, Igor Larionov, Alex Kazatanov, Sergei Makarov and Vladimir Krutov. As Canadians, we saw them as invincible machines who we all thought we’d lose to big time or have to put in a hell of a fight to win, as we did at the 1972 Summit Series and the 1984 Canada Cup.

The film also focuses on the team being instrumental during the Cold War. As many may remember, there was the ‘free world’ led by the United States and the Communist world led by the U. S. S. R. or Soviet Union as we commonly called it. Both countries were bitter enemies and both sought to defeat the other. The people were left paralyzed with fear feeling a war between the two might strike any day especially as each country increased its nuclear warheads. As far as sport went, it was in that arena where the Cold War was a common scene of rivalry. The Soviet Union as well as the other Soviet-allied nations of the Eastern Bloc wanted to use sport as a showcase of Communism’s superiority. The USA/USSR rivalry was always the biggest rivalry at any Olympics. The US had their winning sprinters, decathletes, boxers, wrestlers, swimmers and figure skaters. The Soviets had their gymnasts, throwers, weightlifters, cross country skiers, pairs figure skaters and especially its hockey team. The USSR saw their athletes as soldiers in the sports arena.

However the film does more than remind us of the times and the USSR’s dominance. It also showed life in the USSR. Life under the rationing system may have been fine before World War II but it was hard after the war especially with the country being devastated at a massive level. It didn’t rebuild well but rationing among its citizen’s still existed. It made for a hard life for most as people lived in crowded houses which might not have included running water. Even Slava Fetisov remembers receiving fish on Thursday. It also showed how the athletes were the privileged ones in the Soviet system while regular citizens had to stand in line-ups for their daily rations. It even showed the weakening of this system to the citizens in the 1980’s which paved the way to the reforms known as Glasnost and Perestroika and the eventual collapse of the USSR in 1991.

Of all the hockey players, the film focuses mostly on Slava Fetisov. Fetisov was discovered by sporting scouts of the government who were hired to search out talent at a young age to train up to Olympic level. That was sport in the Soviet Union: children were scouted out, analyzed physically for future athletic potential, and taken to central training facilities to train eleven months a year up to Olympic level. As cruel and inhumane it was for the USSR to do that, it worked and the USSR often had the biggest Olympic medal haul during that time. However the USSR cherished winning in ice hockey the most. In fact there was one propaganda song sung by boys about hockey where they sang lyrics like: “Real men play hockey. Substandard men don’t play hockey.” It was in the hockey stage where they could best show the world Communism’s prowess. It succeeded with winning a massive number of World Championships and eight Olympic golds out of the team’s ten Olympic appearances.

The documentary shows another side of the Soviet hockey team. We all saw the Soviets to play hockey like machines. What we would learn in that documentary is that the Soviets were not only prepared to have the brawn for the game but they were also prepared to have the smarts for the game as they were taught strategies by chess players. They were even taught ballet by some of the top ballet instructors. It wasn’t just tough training they went through but smart training too. What came of it was a play that was not only powerful and effective for winning but a play of style and finesse. Hard to believe none of us Canadians noticed that. Maybe if we weren’t so charmed by all this hockey fighting in the NHL, we would’ve noticed.

The documentary showed another aspect of the Soviet players that we missed all along. Sure, we saw the team as machines but the team was like a family. Slava Fetisov, Tretiak, Larionov, Makarov, Krutov, Kazatonov, they all saw each other as brothers. Of course when your taken from your own home and trained at a location thousands of miles away eleven months of the year, it should be natural to do so. It not only helped in making them better players but it helped with the players knowing their playing style inside out and make them a winning combination on the ice. A reminder that team chemistry was as essential to the success to the Soviet team as it is in practically any team sport. That was one of the qualities coach Anatoliy Tarasov— USSR hockey coach from the 1964 to 1972 Olympics– invested into the Soviet hockey team.

However the film also shows some darker sides of the Soviet team. It begins however on a positive note with Fetisov’s first experiences being coached by Tarasov in the 70’s. Tarasov wasn’t just simply a strict coach but he also played the role as a father figure to the team. Tarasov also helped develop key qualities in the team–speed, grace, teamwork, and patriotism– that became the blueprint of Soviet hockey and helped create their dynasty. However after Tarasov was fired, Viktor Tikhonov was brought in as coach. The Miracle On Ice game of 1980 really hit the Soviets hard not only as a loss of a gold medal but also what appears to be a turning point for Tikhonov. Tikhonov became a lot more ruthless to the players and trained them harder. You can understand why the Soviet players have a disgusted look on their face whenever you mention the Miracle On Ice game and don’t want to talk about it. It was not only a defeat for them but that also marked the time when Tikhonov became more ruthless. He dominated control over the players’ lives. He even cut players from the Soviet team if he sensed they might defect. One example of Tikhonov’s control was when one player’s father was dying. Tikhonov wouldn’t allow him to see his dying father. Things even got so frustrating for Slava at one point, he ran away from the national team to spend time with Tarasov. Here in the documentary none of the players have a positive thing to say about Tikhonov.

The documentary showed that even though the Soviet team was highly acclaimed by the government for their prowess, they were also under heavy scrutiny by the government. Tikhonov wasn’t the only one nervous about possible defections because of the temptation of the NHL. We should remember it was commonly expected that athletes from communist countries were expected to be proud to compete for national glory and reject temptations of money. The team as well as other elite Soviet athletes were allowed to hold Soviet passports: something most Soviet citizens were denied. They were however only allowed to hold them for when they were to attend a competition. Once they arrived back in the USSR, they had to hand them back. Members of the KGB traveled with them in case one member planned to defect. There was a fear that one defection could set off a wave. It reminds us for all their glory and special treatment from the government, they were puppets under a system with a huge eagle eye over them. In fact Tretiak may have been the greatest goalie ever but he was never once allowed to play for the NHL in his whole career.

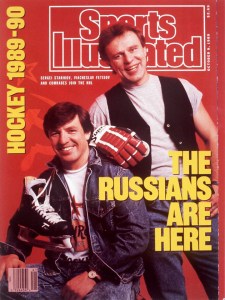

The documentary also shows when the bubble eventually did burst and Soviets eventually did find their way into the NHL. It all started when a junior player by the name of Alexander Mogilny decided to defect in May of 1989. Eight players including Fetisov soon followed. The arrival of such players was met with excitement for some NHL fans while others were more forbidding like Don Cherry who didn’t want any at all. However things weren’t easy. Even though Glasnost and Perestroika were starting to happen, Soviet athletes were still under scrutiny. Fetisov’s professional career in the NHL was monitored. As for play, Fetisov did not adjust too well to new life in the NHL. He learned right in his first game how the NHL was a different kind of play, especially when it came to fighting. His wife Ladlena had some challenges fitting in with the other wives of her husband’s NHL teammates. The struggle was common for a lot of Soviet players trying to adjust to NHL play. Nevertheless things eventually did pay off for Fetisov as he was with the Red Wings in 1997 the same time as Larionov and three other younger Russians. The team was able to get a chemistry of their own and they won the Stanley Cup. The team was able to bring the Stanley Cup to Moscow’s Red Square that year but not without challenges such as clearing things up after a post-victory limousine incident and negotiating with the Russian government.

The documentary ends with what has happened since. Fetisov has become a member of the Russian political party, a Minister of Sport in Russia and even part of Russia’s bidding team in 2007 for the Sochi Olympics in 2014. Tretiak is simultaneously the current President of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation and runs his own goalie school in Toronto which is considered physically punishing by most and very restrictive to whom is admitted. Tikhonov was given countless honors like the Orders of Honor and Merit in Russia and was even a nominee for the Olympic Order. The lives of all the hockey players living and deceased are also focused on at the end.

However the most notable end is the focus on the end of Soviet hockey. As you know the USSR collapsed in 1991. Surprisingly Tikhonov mellowed down in his coaching style afterward but it was still successful enough to bring the team of former Soviets under the name The Unified Team their last gold medal in 1992. The Soviet dynasty ended with as much of a bangs as it began with at the 1956 Olympics. Team Russia has been a different story. Russia continues to churn out top talents and top players. However Russia has never won Olympic gold. Silver in 1998 and bronze in 2002 but that’s it. They didn’t even have it together during Sochi when they lost their quarterfinal to Finland. Leaves you wondering when you remember that talk of the Soviet’s team chemistry if that’s what’s missing with the Russian team. The film ends showing Alexander Ovechkin, the current Russian phenomenon, playing a shootout game for a Washington TV station. A bit of trivia: Ovie was just two weeks short of his sixth birthday when the USSR collapsed. As he plays his game for the TV crew, we hear Slava saying something’s missing in Russian hockey. You’re left feeling that same way too.

One of the funny things of the documentary is that it will remind a lot of Canadians of the inferiority complex Canadians had to endure with in the 1980’s and maybe even the late 1970’s. Already Canadians were going through an inferiority complex of being made to feel second-fiddle to the Americans ever since the inclusion of cable TV bringing American entertainment into our living rooms. Adding to the feelings of inferiority to Canadians was seeing the Soviets excel in hockey. It was often a case of Olympic rules as the best Canadian players were professionals who were ineligible to compete in the Olympics. The best Soviet players however fit within the Olympic rules and were thus eligible to compete at the Olympics Games while the Canadian team at every Olympics during that era always fielded a diluted version of our very best. The Soviets almost always came on top while the Canadian team always fell short. Even when Canada got out its best pros for the Canada Cup, Canada would still face tough challenges from the Soviets as they were total machines and would almost always dominate over the Canadians. You can understand why Canadians cherish the memory of the victory at the 1972 Summit. You can also understand why the Americans hold the 1980 Miracle On Ice close to their hearts. Being second to the Soviets in what is ‘our game’ bit hard and left us down for a long time.

The film also brought back a lot of memories not just of the Soviet team but also how many of us remember the changes of Glasnost and Perestroika that were happening of the late-80’s and early 90’s. It even reminded us of the sports personalities at the time such as Brian Williams, Ron MacLean, Don Cherry, Don Wittman and Al Michaels. It also reminds us of many memorable moments in hockey. In fact it brought back the memories when I remember first hearing of Mogilny’s defection. Who would have thought that would be the beginning of the end?

Another unique thing is that it does something that was never done with the North American television stations before. It humanized the Soviet team. It reminded us behind the strong stoic Soviet team, they were human beings that went through a lot of difficulties. They had human heartbreak of their own. One example when Slava was in a car crash in 1985 that killed his 18 year-old brother. He went through a period of his live when e just didn’t want to live. Even Slava’s talk about his frustration with Tikhonov to the point he runs away to Tarasov showed that even these tough, stoic players had a breaking point of their own. To think all us North Americans saw in the Soviets were machines.

If there was one glitch in this documentary, it’s that Gabe Polsky sometimes does a bit of playing around with the interviews. In fact I remember seeing at the beginning him trying to ask Slava some questions while he’s on a phone call. It’s no wonder Slava flipped him the tweeter after the second question. We see Polsky do a few other stunts too. It’s a question if it was really worth it.

Another glitch is that the film was first released in the middle of 2014 and there was some information either missing or failed to update since. One missing piece of information is Tikhonov’s death in November of 2014. Another piece is of the Sochi Olympics where Fetisov was one of the Olympic flagbearers during the opening ceremony and Tretiak was the final torchbearer along with pairs figure skater Irina Rodnina whom herself is also a three-time Olympic champion and considered the best ever in an event known for Soviet dominance.

Red Army is an intriguing documentary that hockey fans will find worth watching. It takes you back to a stellar dynasty and a unique time. It will also show you a side of them you may have missed during their heyday.