The first documentary I saw at this year’s VIFF was Free Leonard Peltier. At a time when Canada has been made to face the music of what they’ve done to Indigenous people, Leonard’s story will remind you that the plight of the people is not strictly a Canadian problem.

The film begins with a group of American Indigenous activists on a travel. They are traveling to Florida in hopes that fellow activist Leonard Peltier be pardoned and freed just as Joe Biden is about to leave the presidency on January 20, 2025. Trying to get Peltier freed from a double-murder from 1975 he denies and most believe he’s wrongfully accused for has been going on for the last half-century. Many believe it’s Leonard’s last chance at any freedom as he just turned 80 years old and he’s ailing.

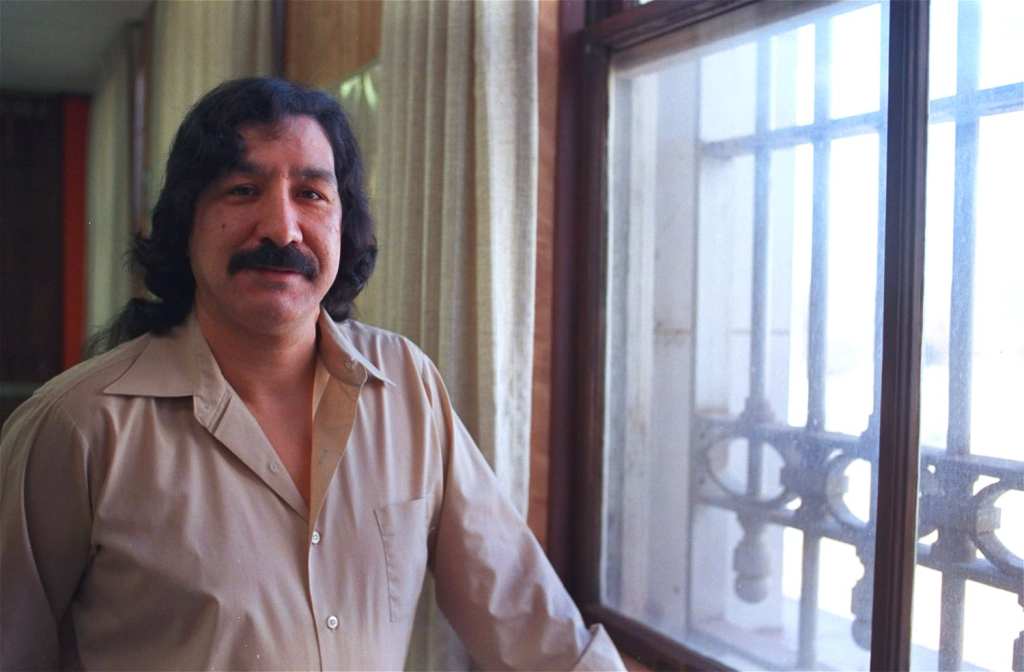

The story of the Leonard Peltier case is told through friends, family and allies of Peltier from the American Indian Movement (AIM). Footage of a 1989 news interview is also shown where Leonard states his own case. Leonard’s early life was like that of many American Indigenous people for over a century. He was born on a reserve in North Dakota to a large family and forced into a Residential School 150 miles away from his place of birth where he and others were taught to assimilate. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) dictated his life and the lives of American indigenous peoples. After he left his schooling behind in 1965, he became a man of various trades doing welding, construction or auto work.

In the late-1960’s, Indigenous activism was growing and the group AIM was founded. Leonard first started with local activism where he was elected tribal chairman of a reservation and he was introduced to AIM from a colleague. His biggest activism in that time was his appearance at 1972’s Trail Of Broken Treaties. Over time, activism became more violent and a group called the Guardians Of the Oglala Nation, or GOON, was founded. Peltier was also involved in violent conflicts and was even charged with attempted murder for an unrelated incident.

During his wait for the trial, FBI agents entered the Pine Ridge Reservation in pursuit of a man named Jimmy Eagle on June 26, 1975 wanted for theft and assault. Two FBI agents named Ronald Williams and Jack Coler were pursuing a Chevrolet with AIM members Peltier, Norman Charles and Joe Stuntz. Charles had met with the two FBI the day before and they told him of their intended pursuit. As the Chevrolet entered the ranch, the three men quickly parked the car and ran out, and that’s when a firefight between the three men and the two FBI ensued. Williams and Coler were shot to death in the shootout. Stuntz was shot to death later that day by a BIA agent. Peltier took Coler’s pistol after he died. The shootout would come to be remembered as the Battle At Wounded Knee.

In the aftermath, the FBI went to arrest three AIM members who were present at the shootout at the time: Dino Butler, Peltier and Robert Robideau. All three were AIM members and all three stole the firearms form the two FBI agents after they were killed. After Peltier was bailed out, he sought refuge in Canada, but it was unsuccessful as Hinton, Alberta RCMP agreed to extradite him back to the United States. In the end, Butler and Robideau were acquitted on grounds of self-defense but Peltier was found guilty. He was sentenced to two life terms and seven years.

In the years that followed would be a long arduous process from friends, family, Indigenous activists, human rights foundations and AIM members to get Leonard Peltier free from a crime he insisted he was innocent of. Over the decades, there was evidence proving that Peltier did not shoot any of the officers. At the same time, the FBI appeared to be playing games as they had one Indigenous women sign an affidavit claiming she was his girlfriend and he confessed to her the shooting. Truth is she didn’t even know him. They also withheld evidence and shred important documents clearing Peltier.

In later decades, Peltier would make pleas of clemency with active Presidents of the United States. Rays of hope first came in 1999 when President Bill Clinton said he would be looking into the Leonard Peltier case and have him cleared and freed. This case for clemency received support from many world leaders like Bishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama. The hope faded as the FBI held a backlash where family of FBI and their allies staged a demonstration claiming that freeing Peltier would do a dishonor to the FBI agents. Their manipulation of making this a Leonard Peltier vs. the FBI case succeeded in keeping him in prison. Peltier continued to make please with clemency with presidents in the years that followed. All would be unsuccessful.

In the 2020’s, Peltier’s health was failing. Painting and drawing, one of his passions he was able to do for decades in prison, was something he could no longer do. Joe Biden was seen as his last chance for clemency in his lifetime, especially since his friends and family knew he would not get any clemency from Trump when he re-enters the White House. Friends and family built a house for Peltier at the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota where he could live after his release. January 19, 2025 was the last day of Biden’s presidency and the supporters at the beginning of the film are waiting to hear the news they hope to hear. Biden reduces Peltier’s sentence from life imprisonment to house arrest. They celebrate knowing he will soon stop being a prisoner.

This is a good documentary as it reminds you of a common problem in the world. Not just in Canada, in the US or in the Americas, but the whole world. The problem is nations being unable to deal with their indigenous peoples or tribal peoples well. Living in Canada, I am very familiar with news stories of how badly the Canadian government has mistreated the Indigenous peoples and how they’re doing a lackluster job to make amends and right past wrongs. The United States is just as guilty of that. They had a residential school system too, they have most of them living on reservations, they have a government that appears unable to listen to them and they’ve even had ‘Indian Wars.’ One can see how the story of the struggle of Leonard Peltier can be something all American Indigenous people can understand and relate to.

The story itself is well-told. I was first introduced to the Leonard Peltier case in 1994 through the music video of “Freedom” by the American band Rage Against The Machine. Peltier’s case has been an inspiration for many songs and films and this documentary is only the latest. In this documentary, we have news footage of the events involving the shootout, arrest, imprisonment and an interview from Peltier in 1989. We also have interviews from surviving friends and family members, Indigenous activists and even attorneys and paralegals who have worked with the Peltier case. The story becomes clear that Peltier’s imprisonment appears to have been used by the FBI just to simply give resolve to the deceased officers’ families and to protect the FBI from looking bad in the eyes of the public. The film’s inclusion of Peltier’s statement of his case makes the shootout look like a case of self-defense. Even though he has always maintained he never shot the officers, he has also stated he would defend himself and his people. One can see why the FBI would fear someone like him.

This is a very informative documentary by Jesse Short Bull and David France. They not only show the Peltier story, but they show how important the Peltier case is to his friends and allies. This is a case that’s taken so long to resolve and it’s at the point friends are even willing to travel from North Dakota to Florida by car in hopes of hearing the good news they’ve been waiting since 1976 to hear. Having AI recreate the incident with film appearing like satellite images re-enacting the heist will get you thinking of the case itself and have you try to make up your own mind about it.

This documentary has received a lot of renown this year. It got a lot of attention at the Sundance festival in January and its biggest acclaim came at the Thessaloniki Documentary Film Festival where it won three awards including the FIPRESCI Prize and the Amnesty International Award.

Free Leonard Peltier is a story about the common racism felt by Indigenous peoples in North America. It’s also a story of hope that what’s wrong can be corrected over time.